Every Story Has a Prelude. Today, Hers Begins. (Part 1 of 3)

Inside the launch of Marjorie Gavan’s The Prelude Girl and the language that turned “placeholder” into power

Photos by M.P.G. Ferraren.

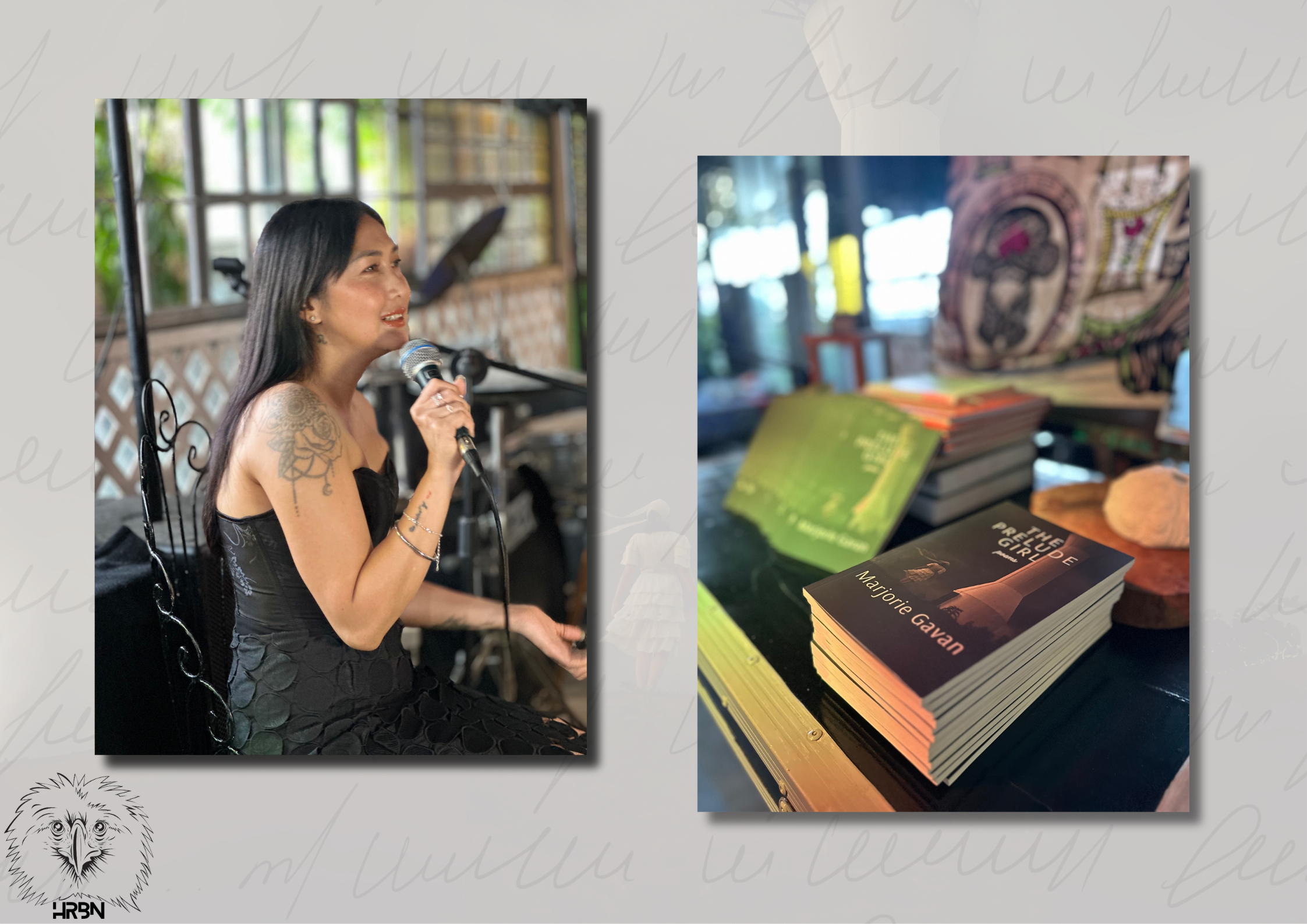

Capri Art Café & Gallery, San Pedro, Laguna — August 30, 2025. The room had the hushed expectancy of a theater before the curtain lifts, murmurs softening against the clink of cups, programs folded and re-folded, friends calling friends to the front row. When Marjorie Gavan stepped up to the mic to launch her debut poetry collection, The Prelude Girl, she didn’t begin with a victory lap. She began with time, two decades of it, and with a word she wanted to change.

“I worked on this for over 20 years,” she told the crowd, candid about the stops and starts that trailed behind the slim volume in her hands. The earliest attempt had a different title—Discontinued Thoughts—and an unruly sprawl of forms: essays, stories, poems. It didn’t hold. This time, she explained, she chose poems only, and she chose a spine of meaning strong enough to carry them: a speaker who survives being the person before “the one.”

Reclaiming a Name

That speaker—“the prelude girl”—was born out of a refusal. “Placeholder,” she noted, is the term culture casually tags on the person you date on the way to somewhere else, a label that reduces a human to utility. She didn’t want that word, not for herself and not for anyone who had ever stood in that waiting room. She wanted a name that gave back agency. “Prelude,” she reasoned, is the introduction before the main act, a poetic frame that acknowledges sequence without erasing worth. “I was a prelude girl,” she said—then widened the circle: women often carry this experience, yes, but men have been preludes, too. The book is for them, and it is for anyone who needs the permission to choose themselves when they are not chosen.

The room—friends, family, former co-workers, even guests who had traveled from Davao—answered with applause. The message was not subtle. “If it happens that you’re not chosen, it doesn’t mean you’re not worth it,” she said. “At the end of the day, you should always choose yourself.”

The Opening Salvo: “I Am Not Your Comfort”

Gavan promised to read, with a caveat. “I’m not a spoken poet,” she laughed, and then opened to the first piece in the collection, “I Am Not Your Comfort.” The poem doesn’t usher readers in with small talk. It plants a sign at the gate: You didn’t come to the right place if what you seek is a warm hand at your back and a stroll on level ground. This is a wasteland, a terrain of vultures, a house of doors that open onto nightmares, a place where you witness what you’ve buried. She read without theatrics, letting the lines do the ferocity. It was a thesis statement, not for cruelty but for clarity—this book will not pad the corners of heartbreak; it will name them.

How a Poet Is Made

“What’s the backstory?” the emcee, Jon, asked. How did this begin? Gavan traced the thread to a grade-school assignment—an early poem in Tagalog that came easily while classmates struggled. She didn’t keep those first efforts; children rarely archive their prophecy. In high school, a classmate’s script drew her toward drama; by college, she was studying journalism. The decisive turn, though, came in 2012 with her first real heartbreak. She didn’t know how else to metabolize it, she said, except to write poems—raw, sometimes diary-like fragments that gradually confessed themselves into shape.

The book we now hold is not a live transcript of pain. Gavan gave herself two months this year to select, rework, and sequence—“I workshopped myself,” she said—reading widely to sharpen the instrument. She cites Sylvia Plath among her anchors, with nods to newer voices that have pressed on her line. The result is a curated arc rather than a chronology: not all that was lived, but what still speaks.

Why Poetry First

Gavan is, by her own admission, a novelist-in-progress. There’s a manuscript, with shades of the supernatural and psychological crime, stalled for now by the author’s stubborn internal editor. “You’ll never finish anything if you criticize it too much,” she observed, then smiled as if to concede she knows exactly what she’s doing. Poetry, this season, offered a project she could finish well: she had draft material, she had a theme, and she had the appetite to pare it to the keenest possible edge.

Choosing the Title—Choosing the Self

Why The Prelude Girl? The question arrived as surely as the book’s title on the screen. Gavan circled back to the word that started it all. She doesn’t want to be remembered as “just a placeholder,” she said; the label might belong to the person who used someone for their own waiting, but it doesn’t map cleanly onto the life that person lived. “Prelude,” in the musical sense, is before the main theme—yet itself is a complete piece. That is the dignity she wanted for the speaker and the reader alike. And for anyone wondering whether exes factor into this—“To be honest, I really don’t care,” she said with a shrug that landed as both grace and boundary. “This is not about them. This is for me.” Art, she reminded us, permits such alchemy: we transform our histories into work that no longer belongs to the past alone.

The Line that Holds the Room

Asked for a favorite, Gavan chose “This Is How I Loved You.” It’s the poem that contains what she calls the book’s gist. She read it last, the cadence tightening as she moved through the scaffold of a relationship built like a ladder, she lowered herself. In one line—already circulating as a signature on social media—the speaker admits: “It was my throne, yet I was the one afraid that you would let it go.” The sentence compresses both adoration and dread, the paradox of elevating someone while fearing the drop that only they can trigger. If you’ve ever loved from the edge of your own seat, you recognized the physics.

Making a Book (and a Moment)

A launch is never just about pages. It’s about the labor you don’t see: the licensing of a cover image years ago, the abandoned drafts, the return to a project when the calendar and courage finally align. From the publisher’s side, we learned the cover photograph—the now-familiar watchtower rising out of storm light—was licensed in 2019, back when the project still bore its earlier, everything-and-the-kitchen-sink working title. There were pauses (procrastination, Gavan confessed with a laugh), but the through line remained: the book wanted to exist. It does now—in paperback on the table, in hardcover with bonus poems, and in e-book for those who prefer pixels to paper.

The ceremonial heart of the afternoon—the unveiling of a large cover on the easel—will be remembered for its levity as much as its symbolism. “On three,” the emcee said; the room counted; someone called a playful reset to make it “more dramatic”; the cloth fell; phones rose. A QR code glowed at the lower corner like a modern sigil: scan to buy, scan to pre-order, scan to tell a friend you were here when the book met its public.

Why this Book, Now

No one needs permission to write about heartbreak; the world is full of breakup songs. But there is something particularly present-tense about The Prelude Girl. It addresses a form of contemporary relationship—almost-love—that thrives in a culture of endless scroll and near-misses, where the architecture of connection can feel provisional by design. Gavan does not ask for closure like a prize; she chronicles the reckoning and leaves the door open for readers to bring their own names to the table. The work is intimate without being confessional in the tabloid sense; it’s deliberate in its music and unsentimental about what survival actually looks like. That mix—tenderness and bite—is what made the audience nod in the places where nodding is a kind of amen.

A Room that Reads

The Q&A that followed swung from craft to community. One guest admired the bravery of reading poems in a culture that is more likely to scroll than to sit still. How would Gavan reach a younger audience—Gen Z, specifically—without losing the book in a sea of short-form content? She answered with gentleness and a grin: pray, experiment, trust the publisher, try TikTok and Reels—and most of all, keep the lines shareable enough to hook attention without losing depth.

The plan is tactical, yes, but also faithful to the spirit of the work: let a few lines do what good lines do—travel.

The Aftertaste of Clarity

If the afternoon had a thesis beyond the poems themselves, it was Gavan’s plainspoken closing argument: Do not measure your worth by someone else’s choice. If you are not chosen, choose yourself. That is the invitation and the insistence at the heart of The Prelude Girl. It is a book built to be carried—physically, the paperback fits the hand; emotionally, the lines fit the pocket of a day when your gut needs a sentence that won’t lie to you.

Part 2 of this three-part feature will step behind the cloth: on the cover that almost predicted the book, on the economics of small-press publishing, and on what happens when an audience becomes a chorus. Part 3 will enter the exchange between poet and readers—the evolving conversation that begins after the final line.

***

The Prelude Girl is available now in paperback; the Kindle edition is live; a hardcover with four bonus poems has joined the lineup. If you were there, thank you for making a room where poetry could breathe. If you weren’t, the book will meet you where you are—and invite you to call yourself by a truer name.